Introduction

This is an introduction to systems of smart contracts. The purpose of these documents is to teach methods of writing large, scalable smart contract back-ends for distributed applications. The reader should be familiar with the basics of smart contract writing, and they should know what accounts, contracts and transactions are, and how to work with them. A good introduction to smart contract development (and a must-read) from the official Solidity site (the language this tutorial is written in) can be found here.

On top of this, we would also recommend checking out the Ethereum wiki. It has links to the above mentioned docs, and a lot of other information as well, such as the contract ABI and the natspec (for documentation). To discuss Eris-specific implementations, the Eris Industries team can be reached on #erisindustries on Freenode or our own support forum

About trust: The systems we study here are designed to be modular, i.e. parts of the code can be replaced during runtime, which in turn makes them inherently trust-ful. Someone must be allowed to make these updates. It is important to know this. If you want to learn how to write small trust-less, automated systems this is not really the place (although many of the principles are the same in both types of systems).

Dependencies

This sequence of tutorials assumes that you have an understanding of the eris tooling to the point we ended in our 101 tutorial sequence.

Smart contracts as services

One way of thinking about smart contracts, and the way we’re going to think about them here, is as extremely basic, stateless web-services. Webservices are units of functionality in a system (the internet), with a well defined API and an identifier (IP address) that can be used to call them. Similarly, a smart contract is a unit of functionality, the public functions exposed by their Solidity contracts is the API, and their public address is the identifier. A web-service is normally called by making an http request, and a contract is called by making a transaction. Also, in most cases everyone is allowed to call them the endpoints are exposed to the public, so security must be handled on a call-by-call basis, and the same thing goes for contracts and their functions. We can even utilize common patterns and architectures, such as for example the microservices architecture.

Finally, before we get started it is important to know this: Writing smart contracts can be tricky. The transition from normal code writing to smart contract writing is not seamless. The environment in which smart contract code runs is different from that of normal code. The analogy with webservices is good, because it makes smart contracts and systems of smart contracts more tangible, and it makes it simpler to use already existing concepts and tools when working with them, but writing the actual code is still difficult.

A simple smart contract

This document is about systems of smart contracts, but we will start by looking at single contracts. This for example is a standard name registry contract. Name registry, or “namereg” contracts generally lets people associate a name with an user account address. This is an example of such a contract:

contract Users {

// Here we store the names. Make it public to automatically generate an

// accessor function named 'users' that takes a fixed-length string as argument.

mapping (bytes32 => address) public users;

// Register the provided name with the caller address.

// Also, we don't want them to register "" as their name.

function register(bytes32 name) {

if(users[name] == 0 && name != ""){

users[name] = msg.sender;

}

}

// Unregister the provided name with the caller address.

function unregister(bytes32 name) {

if(users[name] != 0 && name != ""){

users[name] = 0x0;

}

}

}

When this contract is called, it will use msg.sender and a provided name as parameters. msg.sender refers to the address of the account that made the transaction. name is a fixed-length string that the sender includes in the transaction data. If the name is not already taken, it will be written into users.

This is a very basic but useful contract. It lets you refer to users by name instead of having to use their public address. It could be used as a basis for almost anything. It could use some more functionality, such as being able to list all the registered users, and maybe also make it possible to get a name by address, and not just address by name, and other things. We’re not going to study namereg contracts here though, we’re going to study systems, so we’ll start with another contract instead:

contract HelloSystem {

}

Deploying and removing contracts

The HelloSystem contract can be deployed as-is without any problems, but once it’s been deployed it will remain on the chain for good. We need a way to remove it. In Solidity, the command for removing (or suiciding) a contract is this: suicide(addr). The argument here is the address to which any remaining funds should be sent. In order to expose this functionality, we need to put it inside a (implicitly public) function. This is what a suicide function could look like in HelloSystem:

contract HelloSystem {

function remove() {

suicide(msg.sender);

}

}

What this would do is to remove the contract when the remove function is called, and it would return any funds it may have to the caller. Needless to say, this is not ideal. Normally when you add a suicide function you want to restrict the access to it. The simplest way of doing it is to store the address of the contract creator when the contract is deployed, and only allow the creator to suicide it. Here is how that could be implemented:

contract HelloSystem {

address owner;

// Constructor

function HelloSystem(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

function remove() {

if (msg.sender == owner){

suicide(owner);

}

}

}

Note that msg.sender is not the same in the constructor as it is in the remove function. The constructor is called when the contract is added, so msg.sender will be the contract creator, but in all other functions it will be the address of the account that is calling it.

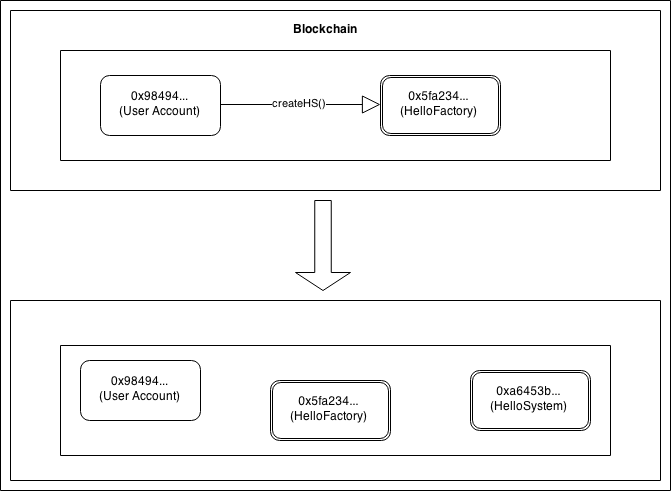

There are several different ways to control how contracts are added and removed. Users can create them by making a create-transaction to the client. Another way is to have contracts create them. Contracts are allowed to create other contracts. Here is one example of a contract that creates a HelloSystem contract.

contract HelloSystem {

address owner;

// Constructor

function HelloSystem(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

function remove() {

if (msg.sender == owner){

suicide(owner);

}

}

}

contract HelloFactory {

function createHS() returns (address hsAddr) {

return address(new HelloSystem());

}

function deleteHS(address hs){

HelloSystem(hs).remove();

}

}

Notice what happened here. We’re creating a new contract but we aren’t adding it to a mapping or other variable, instead we just create it and pass its address back to the caller. We need the deleteHS function because the creator of all the HelloSystem contracts is HelloFactory, which means that HelloFactory is the only contract (or account) that is allowed to remove them.

Account permissions and contract dependencies

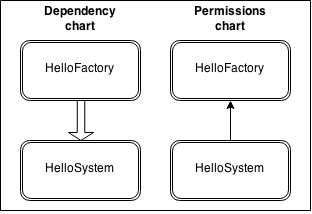

When it comes to the relations between different parts of the system, there are two things we have to keep track of:

1) The dependencies in terms of code

2) The dependencies in terms of permissions

If we look at HelloFactory we can see that HelloSystem is a dependency because HelloFactory is calling functions on that contract. HelloSystem, on the other hand, does not need to call any functions on HelloFactory. When it comes to permissions it is the other way around; HelloFactory will allow calls from any account whereas HelloSystem only accept calls that are made from one single account, namely that of its owner (which in this case is a HelloFactory contract account).

We need to use permissions like this because each contract is a separate account that can be called by any account in the system. Even when we include a contract in the source file of another contract as with HelloFactory, each new contract will still be created as a separate, new contract account that is unrelated to its factory except for any references we might add ourselves.

A simple banking system

We’re now going to make a simple bank account contract that lets people deposit and withdraw money (Ether). We’re going to start by putting all the blockchain logic in one single contract.

contract Bank {

// We want an owner that is allowed to suicide.

address owner;

mapping (address => uint) balances;

// Constructor

function Bank(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

// This will take the value of the transaction and add to the senders account.

function deposit() {

balances[msg.sender] += msg.value;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(uint amount) {

// Skip if someone tries to withdraw 0 or if they don't have enough Ether to make the withdrawal.

if (balances[msg.sender] < amount || amount == 0)

return;

balances[msg.sender] -= amount;

msg.sender.send(amount);

}

function remove() {

if (msg.sender == owner){

suicide(owner);

}

}

}

This contract will let other accounts deposit and withdraw token balances, but it does not scale very well. Let’s say we run a DApp that uses this contract. Eventually we may have a lot of users, and they would probably start requesting new features. Maybe they have other funds (like smart contract-constituted altcoins) and would like to keep everything under the same umbrella. We could just extend the UI to point to these other contracts as well, and manage everything like that, but everything would be disconnected. People would have to use multiple user names, multiple accounts, etc. At some point we would probably want to encapsulate some of the logic into contracts. Unfortunately, our users would still have to call the bank contract directly because it checks the caller address in both the deposit and withdraw functions, which means we can’t really use a proxy account. Another problem is that the functions has no return values, so a contract that calls the bank can’t really know if its calls succeeded or not.

If we want the bank contract to be more suited for a system, we could change it into something like this:

contract Bank {

address owner;

mapping (address => uint) balances;

// Constructor

function Bank(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

// This will take the value of the transaction and add to the senders account.

function deposit(address customer) returns (bool res) {

// If the amount they send is 0, return false.

if (msg.value == 0){

return false;

}

balances[customer] += msg.value;

return true;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(address customer, uint amount) returns (bool res) {

// Skip if someone tries to withdraw 0 or if they don't have

// enough Ether to make the withdrawal.

if (balances[customer] < amount || amount == 0)

return false;

balances[customer] -= amount;

msg.sender.send(amount);

return true;

}

function remove() {

if (msg.sender == owner){

suicide(owner);

}

}

}

Now let us make a simple fund management contract that takes a bank contract address as a parameter. It also deploys the bank contract automatically and keeps track of it.

// The bank contract

contract Bank {

// All the logic from the bank contract.

...

}

contract FundManager {

// We still want an owner.

address owner;

// This holds a reference to the current bank contract.

address bank;

// Constructor

function FundManager(){

owner = msg.sender;

bank = new Bank();

}

// Attempt to deposit the given 'amount' of Ether to the account.

function deposit() returns (bool res) {

if (msg.value == 0){

return false;

}

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract. We pass msg.value along as well.

bool success = Bank(bank).deposit.value(msg.value)(msg.sender);

// If the transaction failed, return the Ether to the caller.

if (!success) {

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

}

return success;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract.

bool success = Bank(bank).withdraw(msg.sender, amount);

// If the transaction succeeded, pass the Ether on to the caller.

if (success) {

msg.sender.send(amount);

}

return success;

}

}

Banking can now be made from the fund manager. It is possible to pass transactions to the fund-manager instead of the bank contract. This is good, because it adds separation of concerns, and it lets us add extra security checks and other things in the fund manager contract that are done before the actual bank contract is called (at least when we have made sure the bank functionality can only be accessed by the fund manager, which we’ll do later). The system is not very modular, however, because we’re stuck with this particular bank contract. What if we want to update the bank contract itself?

What we should be doing here is work with an interface instead and allow the bank account to be swapped out:

contract FundManager {

address owner;

// This holds a reference to the current bank contract.

address bank;

// Constructor

function FundManager(){

owner = msg.sender;

// We still start with the normal bank.

bank = new Bank();

}

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

// Add a new bank address to the contract.

function setBank(address newBank) constant returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

bank = newBank;

return true;

}

// ********************************************************************************

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function deposit() returns (bool res) {

if (msg.value == 0){

return false;

}

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract. We pass msg.value along as well.

bool success = Bank(bank).deposit.value(msg.value)(msg.sender);

// If the transaction failed, return the Ether to the caller.

if (!success) {

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

}

return success;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract.

bool success = Bank(bank).withdraw(msg.sender, amount);

// If the transaction succeeded, pass the Ether on to the caller.

if (success) {

msg.sender.send(amount);

}

return success;

}

}

This system is better, but it is still not very flexible; nor is it safe. For one thing, we only allow the owner to set the bank. We might want a more sophisticated system for assigning permissions. We also need to protect the bank contract functions, of course, so they become accessible only from the fund manager.

More permission-management

First, let us add some simple user permission levels to the fund manager. We only use the value 0 for no permissions, and 1 for banking permissions at this point, but we use a uint instead of a bool so that we may extend it later. We will also make it possible to set the owner of the bank contract, so that we can set the owner address at any time instead of automatically assigning when the contract is deployed.

contract Bank {

address owner;

mapping (address => uint) balances;

// Constructor

function Bank(){

}

function setOwner(address newOwner) returns (bool res) {

// IMPORTANT: We don't want to allow the user to be reassigned, except maybe by the

// current owner.

if (owner != 0x0 && msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

owner = newOwner;

return true;

}

// This will take the value of the transaction and add to the senders account.

function deposit(address customer) returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

balances[customer] += msg.value;

return true;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(address customer, uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

// Skip if someone tries to withdraw 0 or if they don't have enough Ether to make the withdrawal.

if (balances[customer] < amount || amount == 0)

return false;

balances[customer] -= amount;

msg.sender.send(amount);

return true;

}

function remove() {

if (msg.sender == owner){

suicide(owner);

}

}

}

contract FundManager {

// We still want an owner.

address owner;

// This holds a reference to the current bank contract.

address bank;

// Permissions

mapping (address => uint) perms;

// Constructor

function FundManager(){

owner = msg.sender;

bank = new Bank();

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

Bank(bank).setOwner(address(this));

// ********************************************************************************

}

// Add a new bank address to the contract.

function setBank(address newBank) returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

bool result = Bank(newBank).setOwner(address(this));

// If we couldn't set ourself as owner, we will not add the bank.

if(!result){

return false;

}

// ********************************************************************************

bank = newBank;

return true;

}

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

// We're responsible for this now that we're the owner of the banks.

function suicideBank(address addr) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return;

}

Bank(addr).remove();

}

// Set the permissions for a user.

function setPermission(address user, uint perm) constant returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

perms[user] = perm;

return true;

}

// ********************************************************************************

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function deposit() returns (bool res) {

if (msg.value == 0){

return false;

}

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

if(perms[msg.sender] != 1){

return false;

}

// ********************************************************************************

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract. We pass msg.value along as well.

bool success = Bank(bank).deposit.value(msg.value)(msg.sender);

// If the transaction failed, return the Ether to the caller.

if (!success) {

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

}

return success;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if ( bank == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

// NEW

// ********************************************************************************

if(perms[msg.sender] != 1){

return false;

}

// ********************************************************************************

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract.

bool success = Bank(bank).withdraw(msg.sender, amount);

// If the transaction succeeded, pass the Ether on to the caller.

if (success) {

msg.sender.send(amount);

}

return success;

}

}

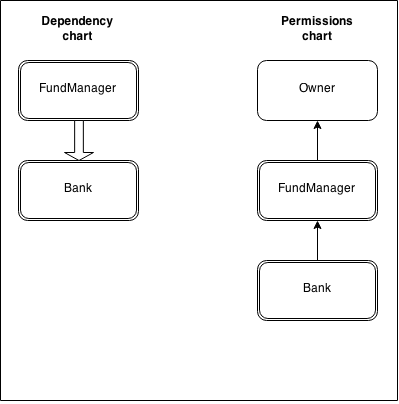

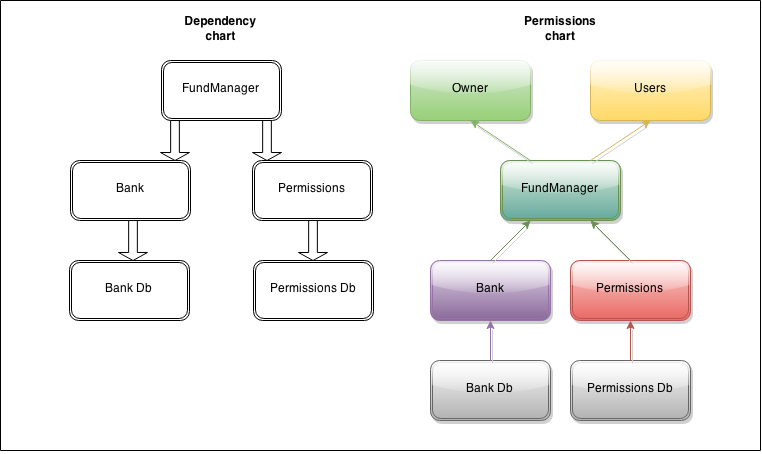

We now have a system that’s similar to HelloFactory and HelloSystem. We can even make a basic dependency chart.

There is more work to do, however. We have not enabled the system for handling multiple different bank types, which was the whole point to begin with. Also, we have not considered the implications of switching the bank account out. What of all the data that’s still in there? We can’t just cut it off and start a new bank, we would have to merge the old balances into the new contract somehow. Also, we would have to make sure we move the actual Ether stored in the old contract. Either that or make sure that the new bank gets permissions to operate on the old one, and does that as part of its functionality.

What we’ve done here is a very common mistake: we did not separate the database from the controller. This is true in the bank contract but also in the fund manager; it keeps the permissions mapping in the same contract that operates on it. What if we want to update the permissions system? We’d have to replace the entire fund-manager contract.

Also, the permissions structure is a bit more complicated now. Not only do we have the single-user permission to remove contracts and such, but we also have a second type of permission, which is to do banking.

At this point we’re gonna stop making patches though, and instead use a model in which some of the basics has been fleshed out.

Systems of smart contracts - the five types model

First of all: Every non-trivial DApp will require more then one contract to work well. There is no way to write a secure and scalable smart contract back-end without distributing the data and logic over multiple contracts. It may be hard to know exactly how to do this, so we’re going to start by dividing contracts up into categories; instead of thinking about them in terms of what they do, we’re going to start thinking about them in terms of what they are. There are many different ways to classify contracts, but we’re going to use what I call “the five types model”. It is a simple model where contracts are divided up into five basic categories:

1) Database contracts

These are used only as data storage. The only logic they need is functions that allow other contracts to write, update and get data, and some simple way of checking caller permissions (whatever those permissions may be).

2) Controller contracts

These contracts operate on the storage contracts. In a flexible system, both controllers and databases can be replaced by other, similar contracts that share the same public api (although this is not always needed). Controllers can be advanced, and could for example do batched reads/writes, or read from and write to multiple different databases instead of just one.

3) Contract managing contracts (CMCs)

The purpose of these contracts is only to manage other contracts. Their main tasks is to keep track of all the contracts/components of the system, handle the communication between these components, and to make modular design easier. Keeping this functionality separate from normal business logic should be considered good practice, and has a number of positive effects on the system (as we will see later).

4) Application logic contracts (ALCs)

Application logic contracts contains application-specific code. Generally speaking, if the contract utilizes controllers and other contracts to perform application specific tasks it’s an ALC.

5) Utility contracts

These type of contracts usually perform a specific task, and can be called by other contracts without restrictions. It could be a contract that hashes strings using some algorithm, provide random numbers, or other things. They normally don’t need a lot of storage, and often have few or no dependencies.

The rationale for this division will be laid out after we’ve tried to apply it to the fund manager system, as it will be a lot more clear then.

The fund management system - take 2

We will now analyze the fund management system using the five types model. It is a very small system so analyzing it will be simple. What we have is the bank component and the fund manager component. The functionality of the bank component is exposed only to the fund manager. The first thing we should be doing is to break the permissions part out of the fund manager, then we should divide the bank and permissions components up into controller and database contracts. This is what we’d get.

Note how the permissions work. The bank does not use the permissions contract; it can still only be used by the FundManager contract. Permission checks will be done like before, except the code will be kept in a separate contract (or two, to be more exact). The two databases can only be accessed by their controllers, and the controllers only by the fund manager. The fund manager in turn does whatever the users tells it to do, ie it is not autonomous in any way. Same thing for the controllers.

Also, this permissions chart is not complete. First of all, the owner could be a user as well and be allowed to do banking. Secondly, we actually have two types of permissions here, banking and administration (the adding and removal of contracts). If we wanted to do this right we would have to divide each contract account up into different sections, depending on the permissions needed to call the code in that block, and use one arrow for each permission type, but we’re not going to that here.

Adding a CMC

Now we have to tie this all together. We need to make sure that the two controller-database pairs finds eachother, and that the fund manager finds the two controllers, but instead of keeping this type of logic in the contracts themselves we will break it out and put it into CMC contracts. If we wanted to do this right we would probably add one CMC for managing the controller-database flow for the bank, one for permissions and an additional one for the system as a whole, giving it a tree-like structure, but for simplicity we’re going to flatten things and go with a standard CMC for everything:

// The top level CMC

contract Doug {

address owner;

// This is where we keep all the contracts.

mapping (bytes32 => address) contracts;

modifier onlyOwner { //a modifier to reduce code replication

if (msg.sender == owner) // this ensures that only the owner can access the function

_

}

function addContract(bytes32 name, address addr) onlyOwner {

contracts[name] = addr;

}

function removeContract(bytes32 name) onlyOwner returns (bool result) {

if (contracts[name] == 0x0){

return false;

}

contracts[name] = 0x0;

return true;

}

function getContract(bytes32 name) constant returns (address addr) {

return contracts[name];

}

function remove() onlyOwner {

suicide(owner);

}

}

There are two things to note here. One is that we have begun to use the modifier keyword. This reduces our code replication and can be tacked onto our functions like you see with onlyOwner above. This is useful in keeping your CMCs clean and well maintained. The other thing to note is that Doug is actually a misnomer. Doug is not one smart contract but many, with numerous components. One of the components is name registration, though, so I tend to call these type of top-level namereg CMCs Doug.

We will use this contract to store the following contracts: “fundmanager”, “bank”, “bankdb”, “perms”, “permsdb”. We’re also going to add links to Doug in all of them and then use it as glue. They’ll call doug to get the address to contracts they need, cast them, and then call the functions. This is how it will work more specifically:

All contracts that are part of this system will extend a DougEnabled contract, that will look like this:

// Base class for contracts that are used in a doug system.

contract DougEnabled {

address DOUG;

function setDougAddress(address dougAddr) returns (bool result){

// Once the doug address is set, don't allow it to be set again, except by the

// doug contract itself.

if(DOUG != 0x0 && msg.sender != DOUG){

return false;

}

DOUG = dougAddr;

return true;

}

}

This logic will be utilized by Doug when addContract is called, to set it. If the contract already has a Doug address, it will return false on setDougAddress, and in that case it will not be added.

function addContract(bytes32 name, address addr) {

if(msg.sender != owner){

return;

}

bool sda = DougEnabled(addr).setDougAddress(address(this));

if(!sda){

return;

}

contracts[name] = addr;

}

Databases will call doug when something tries to modify them. This would be how the bank does it:

function deposit(...) {

...

address db = Doug(DOUG).getContract("bankdb");

if(msg.sender != db){

return;

}

...

}

Controllers would use Doug to check to make sure the caller is “fundmanager”, and it would also use Doug to get the address to the respecive database to do reads, and the fundmanager would use Doug to get the address to the bank and permission controllers. Also, again using this CMC would be somewhat like craming everything into the global namespace. There is no real structure which is usually wrong but this is a small system and we want to keep things simple. In most systems you’d have more then one CMC and also more advanced CMC logic.

The Finished Contracts

This is all the contracts in their final form.

// Base class for contracts that are used in a doug system.

contract DougEnabled {

address DOUG;

function setDougAddress(address dougAddr) returns (bool result){

// Once the doug address is set, don't allow it to be set again, except by the

// doug contract itself.

if(DOUG != 0x0 && msg.sender != DOUG){

return false;

}

DOUG = dougAddr;

return true;

}

// Makes it so that Doug is the only contract that may kill it.

function remove(){

if(msg.sender == DOUG){

suicide(DOUG);

}

}

}

// The Doug contract.

contract Doug {

address owner;

// This is where we keep all the contracts.

mapping (bytes32 => address) public contracts;

modifier onlyOwner { //a modifier to reduce code replication

if (msg.sender == owner) // this ensures that only the owner can access the function

_

}

// Constructor

function Doug(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

// Add a new contract to Doug. This will overwrite an existing contract.

function addContract(bytes32 name, address addr) onlyOwner returns (bool result) {

DougEnabled de = DougEnabled(addr);

// Don't add the contract if this does not work.

if(!de.setDougAddress(address(this))) {

return false;

}

contracts[name] = addr;

return true;

}

// Remove a contract from Doug. We could also suicide if we want to.

function removeContract(bytes32 name) onlyOwner returns (bool result) {

if (contracts[name] == 0x0){

return false;

}

contracts[name] = 0x0;

return true;

}

function remove() onlyOwner {

address fm = contracts["fundmanager"];

address perms = contracts["perms"];

address permsdb = contracts["permsdb"];

address bank = contracts["bank"];

address bankdb = contracts["bankdb"];

// Remove everything.

if(fm != 0x0){ DougEnabled(fm).remove(); }

if(perms != 0x0){ DougEnabled(perms).remove(); }

if(permsdb != 0x0){ DougEnabled(permsdb).remove(); }

if(bank != 0x0){ DougEnabled(bank).remove(); }

if(bankdb != 0x0){ DougEnabled(bankdb).remove(); }

// Finally, remove doug. Doug will now have all the funds of the other contracts,

// and when suiciding it will all go to the owner.

suicide(owner);

}

}

// Interface for getting contracts from Doug

contract ContractProvider {

function contracts(bytes32 name) returns (address addr) {}

}

// Base class for contracts that only allow the fundmanager to call them.

// Note that it inherits from DougEnabled

contract FundManagerEnabled is DougEnabled {

// Makes it easier to check that fundmanager is the caller.

function isFundManager() constant returns (bool) {

if(DOUG != 0x0){

address fm = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("fundmanager");

return msg.sender == fm;

}

return false;

}

}

// Permissions database

contract PermissionsDb is DougEnabled {

mapping (address => uint8) public perms;

// Set the permissions of an account.

function setPermission(address addr, uint8 perm) returns (bool res) {

if(DOUG != 0x0){

address permC = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("perms");

if (msg.sender == permC ){

perms[addr] = perm;

return true;

}

return false;

} else {

return false;

}

}

}

// Permissions

contract Permissions is FundManagerEnabled {

// Set the permissions of an account.

function setPermission(address addr, uint8 perm) returns (bool res) {

if (!isFundManager()){

return false;

}

address permdb = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("permsdb");

if ( permdb == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

return PermissionsDb(permdb).setPermission(addr, perm);

}

}

// The bank database

contract BankDb is DougEnabled {

mapping (address => uint) public balances;

function deposit(address addr) returns (bool res) {

if(DOUG != 0x0){

address bank = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bank");

if (msg.sender == bank ){

balances[addr] += msg.value;

return true;

}

}

// Return if deposit cannot be made.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

function withdraw(address addr, uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if(DOUG != 0x0){

address bank = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bank");

if (msg.sender == bank ){

uint oldBalance = balances[addr];

if(oldBalance >= amount){

msg.sender.send(amount);

balances[addr] = oldBalance - amount;

return true;

}

}

}

return false;

}

}

// The bank

contract Bank is FundManagerEnabled {

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function deposit(address userAddr) returns (bool res) {

if (!isFundManager()){

return false;

}

address bankdb = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bankdb");

if ( bankdb == 0x0 ) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract. We pass msg.value along as well.

bool success = BankDb(bankdb).deposit.value(msg.value)(userAddr);

// If the transaction failed, return the Ether to the caller.

if (!success) {

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

}

return success;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(address userAddr, uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if (!isFundManager()){

return false;

}

address bankdb = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bankdb");

if ( bankdb == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract.

bool success = BankDb(bankdb).withdraw(userAddr, amount);

// If the transaction succeeded, pass the Ether on to the caller.

if (success) {

userAddr.send(amount);

}

return success;

}

}

// The fund manager

contract FundManager is DougEnabled {

// We still want an owner.

address owner;

// Constructor

function FundManager(){

owner = msg.sender;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function deposit() returns (bool res) {

if (msg.value == 0){

return false;

}

address bank = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bank");

address permsdb = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("permsdb");

if ( bank == 0x0 || permsdb == 0x0 || PermissionsDb(permsdb).perms(msg.sender) < 1) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract. We pass msg.value along as well.

bool success = Bank(bank).deposit.value(msg.value)(msg.sender);

// If the transaction failed, return the Ether to the caller.

if (!success) {

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

}

return success;

}

// Attempt to withdraw the given 'amount' of Ether from the account.

function withdraw(uint amount) returns (bool res) {

if (amount == 0){

return false;

}

address bank = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("bank");

address permsdb = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("permsdb");

if ( bank == 0x0 || permsdb == 0x0 || PermissionsDb(permsdb).perms(msg.sender) < 1) {

// If the user sent money, we should return it if we can't deposit.

msg.sender.send(msg.value);

return false;

}

// Use the interface to call on the bank contract.

bool success = Bank(bank).withdraw(msg.sender, amount);

// If the transaction succeeded, pass the Ether on to the caller.

if (success) {

msg.sender.send(amount);

}

return success;

}

// Set the permissions for a given address.

function setPermission(address addr, uint8 permLvl) returns (bool res) {

if (msg.sender != owner){

return false;

}

address perms = ContractProvider(DOUG).contracts("perms");

if ( perms == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

return Permissions(perms).setPermission(addr,permLvl);

}

}

Usage

This is how this system would be deployed:

- Deploy Doug.

- Deploy all the other contracts (doesn’t matter in which order it’s done), register them with Doug.

- Optionally, call the fundmanager to set your own permission to 1.

To run the system, just add permissions for people and start sending money to the fund manager.

Extending the system

If we want to add more banks to the system we could do that. The Doug contract makes it easy to add and remove contracts. We could also extend the already existing code quite easily even when the system is running. Let’s say we want to add logging to the bank. The idea is that a short log entry should be written when someone makes a deposit or withdrawal. The entry should contain the transaction type (deposit or withdraw), the amount of Ether, and the timestamp. How would we do that?

In this system it would be simple. Trivial even. This is how we could do it:

- Keep fundmanager as is.

- Add the logging to a new bank controller. It would have the exact same code as the current one except it would also log.

- Register the new controller with Doug under the name “bank”

- Start using.

We could actually add the log as a separate contract and register it with Doug, and use it that way. We could even give it a controller and database part like the other contracts, and maybe let the permissions manager and other components make use of it too.

Another thing that could be done, which would improve the system a lot, is to link a lot of the owner stuff to permissions instead. What if we introduce 4 permission levels, where each level includes the permissions of all lower levels as well:

0 means no permissions.

1 means bank user permissions.

2 means permissions to add bank permissions to others as well.

3 highest permission level means being allowed to do anything, such as removing contracts, and also to give this permission to others.

We could have the permissions contract automatically assign permission level 3 to the creator. This would be as easy as adding this constructor to the Permissions contract:

function Permissions() {

perms[msg.sender] = 4;

}

What we’d do next is replace some of the checks for (msg.sender == owner) with permissions checks.

Current setPermissions function in the fund manager.

// Set the permissions for a given address.

function setPermission(address addr, uint8 permLvl) constant returns (bool res) {

if (msg.caller != owner){

return false;

}

address perms = Doug(DOUG).getContract("perms");

if ( perms == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

return Permissions(perms).setPermission(addr,permLvl);

}

New

// Set the permissions for a given address.

function setPermission(address addr, uint8 permLvl) returns (bool res) {

address perms = Doug(DOUG).getContract("perms");

if ( perms == 0x0 ) {

return false;

}

Permissions pc = Permissions(perms);

uint8 userPerm = pc.getPermission(addr);

if(userPerm < 3) {

return false;

}

return pc.setPermission(addr, permLvl);

}

Cost benefit analysis

Given all of the extra contracts and indirection that’s needed, we may ask if it’s even worth doing. For example, if all I want to do is to deposit some money, why do i have to call one contract that calls a second contract that calls a third one, also doing calls to a fourth one all the way?

There are some things to consider when deciding how the system should be designed. Modularity is good, but it comes with a price. All this indirection means more calls and more processing, which means the cost for executing the code is higher, and the added bytecode makes storing the contracts more expensive.

There is also the matter of trust, but I treat that in the beginning of the document.

Coming next

Next, let us look at what we call action-driven architecture.